What is Mesmerism?

The phrase “animal magnetism” evokes mental images of emanating sensuality, of raw primal attraction. Colloquially, this is what animal magnetism means. However, animal magnetism once held a very different definition. There was a time, in fact, when it was thought, albeit by a small group of believers, that animal magnetism would completely change the human experience. For its advocates, animal magnetism seemed like the solution for a host of diseases, deficiencies, and sources of human suffering.

The bizarre saga through which the phrase “animal magnetism” was coined also originated the term “mesmerism,” which is synonymous today with hypnotism.

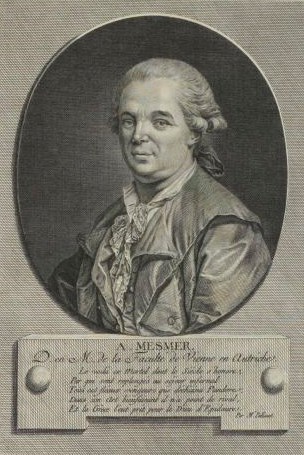

Who was Franz Mesmer?

Mesmerism derives from the name of an eighteenth century scientist. Franz Anton Mesmer was born in Southern Germany in 1734. He was educated in Latin at a young age and spent his adolescence in a series of Jesuit schools, presumably in preparation for Catholic priesthood. (1)

Instead, Mesmer began to turn his eye towards the medical field. After briefly pursuing a law degree, Mesmer submitted a doctoral thesis at the age of thirty-two. This thesis is where Franz Mesmer’s unique eccentricities began to show. Borrowing heavily from the works of Sir Isaac Newton and the physician Richard Mead, Mesmer’s thesis explored the hypothesis that the movements of the heavenly bodies have an effect on the physical health of living creatures. Mesmer would suggest that the planets’ gravitational influence was affected upon a mysterious fluid energy running through the human body. He would initially dub this theory “animal gravitation.” Eventually, he would rename this concept as “animal magnetism.” (2)

It was, in the eighteenth century, not altogether strange to refer to energy or electricity as a “fluid.” It is likely, in fact, that Mesmer’s “fluid” originated from a reading of Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica, which described electricity, a concept not yet understood, in terms resembling liquid. We know that Newton’s work was widely popular and influential within eighteenth century scientific circles and that Mesmer was heavily influenced by it.

After completing his doctoral thesis, Mesmer married a wealthy Viennese widow and began interacting with the Viennese social scene. He established his medical practice in Vienna and began hosting important Viennese social movers at his expansive mansion and gardens. During this time he even became acquainted with a young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, patronizing the up and coming composer who was just twelve at the time. (3)

Dissatisfied by the results affected by medical procedures during his time and inspired by the reported success of Jesuit priest Maximilian Hell in the area of magnet therapy, Mesmer returned to the theories he espoused in his doctoral thesis. (4)

Read More Weird History: The Pied Piper Story: What Really Happened to the Children of Hamelin?

What did Franz Mesmer Do?

A young woman by the name of Franziska Oesterline presented herself to Mesmer. He reported her as suffering from nausea, convulsions, rage, hysteria, and a number of other symptoms culminating in what he termed a “convulsive malady.” Mesmer attempted treating his theorized source of Oesterline’s illness: a blockage of that mysterious fluid which regulates “animal magnetism.” Using magnetic rods and various forms of stimulation and touch, Mesmer seemed to have cured Franziska Oesterline of her malady. (5)

Believing himself to have discovered something revolutionary, Mesmer began introducing magnetic therapies to the Viennese public. In some instances, he would tightly press his patients’ knees together in between his own, in some patients he would perform arcane movements in the air with his hands or with metal implements, in some cases he would run his hands along his patients’ limbs, hoping to stimulate a desired movement in animal magnetism. He even invented his own musical instrument, a bizarre glass instrument referred to as a “glass armonica,” which he believed could affect the magnetic fluid of the human body. (6)

Mesmer’s popularity began to bloom and with it came eccentric new ideas for treating patients. Now tasked with treating a variety of patients, sometimes dozens at a time, Mesmer came to believe that he could “magnetize” objects by simply touching them. He would magnetize his patients’ beds so that they could be treated in their sleep and he would magnetize objects in his home so that patients could benefit from touching them. Eventually, he even invented a bizarre object intended to help treat up to thirty patients at once. Called a “baquet,” this tool was a large vessel filled with iron shavings which Mesmer would infuse with “animal magnetism.” Protruding from the baquet were a number of metal rods which patients could grasp to allow the magnetism to enter their bodies. (7)

His apparent success attracted a great deal of attention and patients, but brought with it doubt and scandal. In 1777, Mesmer attempted to treat a blind woman by the name of Maria Theresia von Paradis. Maria Theresia was a well-known pianist, so it generated quite a lot of buzz when Mesmer claimed to have restored her sight. What ensued after this is unclear. Most accounts agree that Maria claimed to have restored vision whilst in the presence of Franz Mesmer, but that when he left the room, or perhaps when treatment ceased, her vision would disappear again. According to some supporters of Mesmer, Maria’s treatment was ongoing and her vision only failed when she was removed from his care by her family. Mesmer’s detractors go so far as to class the whole incident as a farce and to even suggest an inappropriate relationship between the middle-aged Mesmer and his teenaged patient.

The distasteful controversy of the Maria Theresia von Paradis incident led Mesmer to relocate. Leaving behind the increasingly skeptical community of Vienna, Mesmer set up shop in Paris. There, he quickly amassed a following of wealthy clientele which included Marie Antoinette. In Paris, Mesmer published a book in French explaining animal magnetism and the principles by which he proposed that it operated.

Before long, though, Mesmer’s far-fetched claims began to inspire familiar skepticism in Paris. Discomfort surrounding his long private healing sessions with female socialites began to mar his reputation. In 1784, King Louis XVI assembled a Royal Commission which was dispatched to investigate Mesmer’s practices. The commission, which included Benjamin Franklin along with a panel of scientists and medical experts, would eventually conclude that the fluid which Mesmer claimed to manipulate simply did not exist. Mesmer’s treatments could not be demonstrated scientifically, and thus were declared unfounded. (8)

Did Mesmerism Work?

How then, did Mesmer seem to alleviate so much suffering in his patients? The answer to this is key in understanding the modern meaning of “mesmerism.” Franz Mesmer stumbled onto a treatment that is still used today to address psychological and behavioral ailments as well as certain types of pain. This treatment is hypnotherapy. Mesmer would often lead his patients in exercises wherein they would claim to feel a mysterious fluid flowing through them; in reality the power of visualization and suggestion would affect their symptoms where possible. This explains why a truly physiological ailment, such as blindness, was beyond Mesmer’s ability. It has also been suggested that some of Mesmer’s success was a result of the so-called “placebo effect.” (9)

Following the commission’s findings, Mesmer lived out the remainder of his life in Switzerland in a sort of pseudo-exile. Although his reputation may forever be that of a “quack,” his career left a marked impression. Hypnotherapy is now a widely recognized practice for treating a limited set of ailments, and phrases like “mesmerize” and “animal magnetism” have found permanent homes in the English vernacular.