Henry II was born in 1133 to “Empress” Matilda and Geoffrey “the Handsome.” Matilda was the daughter of Henry I, King of England, and the granddaughter of William the Conqueror. This meant that young Henry was born with a unique destiny. As Matilda grappled against her cousin, Stephen of Blois for the throne of England, her son slowly acquired knowledge of political and military strategy, alongside lordly titles. In time, peace was obtained with Stephen of Blois via the treaty of Wallingford which allowed Stephen to rule England until his death, at which time he would leave the throne to Henry II. Shortly after the treaty was agreed upon, Stephen died, thus beginning the 35 year reign of a Plantagenet king whose descendants would rule England for more than 300 years.

More medieval history: The Travels of Sir John Mandeville

Who was Henry II? The Father of the Plantagenet Kings

And who better to start off this sprawling dynasty than Henry? He was a clever political maneuverer and a military strategist who had cut his teeth in early adolescence on a civil war that ultimately ended with him on the throne. In many respects, Henry II was a brilliant ruler. That his descendants sat on England’s throne for so many years is a testament to that in itself. But his reign was not without its complications.

For one thing, Henry II had eight children through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. This should have been an asset that secured the future of his lineage, but Henry’s sons began to create problems at a young age. Dissatisfied with the land and titles handed down from their father, Henry the Young King, who was crowned as a nominal ruler alongside his father at just 15 years of age but never allowed any actual power of governance, rebelled against Henry II. Two of his brothers, along with his mother, Eleanor, joined in this revolt. This would not be the last time Henry II’s family rose against him. In fact, several years later, Henry the Young King would die of dysentery during another revolt against his father. After Henry II’s death, his empire would crumble under the leadership of his youngest son, John and subsequent generations would devote their reigns to a desperate struggle to reclaim the expansive power that they once held under Henry II.

All of this is to say that Henry II’s reign was fraught with conflict, despite his talent for leadership. Not least among these conflicts was Thomas Becket.

More fascinating history: The Dog Who Became a Saint

The Troublesome Priest

Church and state is a power struggle as old as time. While countless kings have evoked a holy mandate to justify their position, the actual role of royal authority versus religious authority on earth has long been a matter of push and pull. Henry II was recorded by historians of his age as a patron of many monasteries. His third son, King Richard I “the Lionheart” is best remembered as a crusader king. Despite this, alongside the revolts staged by his sons, Henry II’s clash with the Church of England remains the most memorable conflict of his reign. This is largely thanks to his relationship with Thomas Becket.

The Archbishop of Canterbury was an important seat of power within the medieval Church of England. This is why, when Archbishop Theobald of Bec died in 1161, the ever-shrewd Henry II saw this as an opportunity to expand his power over the church. He thought that by appointing a close friend to this role, he could bring the Church of England under his power and avoid future opposition from the holder of this often-troublesome position. His choice was Thomas Becket. Becket was Henry II’s English Chancellor. He had acted as a tutor to Henry’s sons and was a trusted ally. Henry imagined that he could appoint Becket as Archbishop while retaining him as his Chancellor, thus keeping the Archbishop as a member of his own court and tightening his grip on the Church of England. Some sources indicate that Thomas Becket really didn’t want this role at all and resisted the appointment. In any case, he was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162. This would prove to be a disastrous decision.

Sources vary with regards to Thomas Becket’s pre-Archbishop lifestyle, with some claiming that he was already a deeply religious soul, and others casting him as a wealthy aristocrat with a penchant for lavish spending. Regardless of Becket’s past lifestyle, Henry II’s assumption that Becket would support his secular authority over the duties of the Archbishop was a costly miscalculation. Becket and Henry began to butt heads almost immediately when Becket resigned the Chancellor position against Henry’s wishes and devoted himself to the Church of England.

Contrary to Henry’s expectations, Becket fought to protect the autonomy and power of the church and, in doing so, became a thorn in Henry’s side. The former friends were now bitter political nemeses. This came to a head in 1164 when Thomas Becket was called before a great council under accusations of contempt for royal authority. He was found guilty and ordered to surrender all personal property. This led to his flight to France where he lived in exile for several years.

More intriguing history: Who is Calafia?

Who Killed Thomas Becket?

Exile might have allowed the animosity between Becket and Henry II to cool off if not for the fact that the scandal had become something of an international political theater. Not content to hide from the vengeful eye of the throne, the exiled Becket used his authority as Archbishop to excommunicate Henry’s political allies. this hatred from a distance might have simmered in this fashion for many more years had the time not come for Henry II to crown his son, Henry the Young King as co-ruler of England.

Traditionally, England’s kings are always crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury. This holy stamp of approval lends legitimacy to their reign and is a key connection in the relationship between royal and church authority. This forced Henry to try and make peace with his exiled former friend. When this failed, Henry the Younger was crowned by the Archbishop of York instead, and the tension between Henry and Thomas Becket finally reached a tipping point. Thomas Becket declared an interdict against the whole of England until the matter was resolved. This banned the entire country from participation in certain rituals of the church. Needless to say, this was a drastic move that forced Henry to negotiate. In the end, Thomas was allowed to return from his exile in 1170, six years after he had initially fled to France.

This was not an amicable reunion. Upon his arrival back in the country of his birth, Becket made short work of provoking Henry and endangering the delicate truce that had allowed him to return. He promptly excommunicated several clergy members, including the Archbishop of York, for their involvement in Henry the Young King’s coronation on the grounds that his rights as the Archbishop of Canterbury had been sidestepped. This was a slap in the face to Henry II who is often misquoted as having cried out “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest!” In actuality, the quote is believed to be: “What miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!”

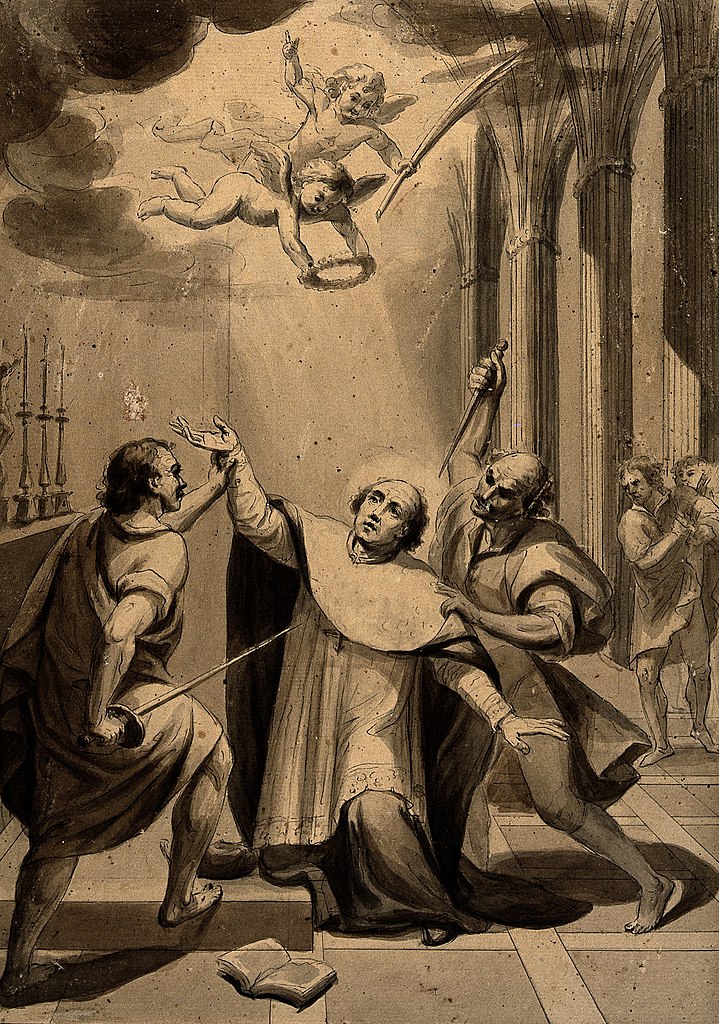

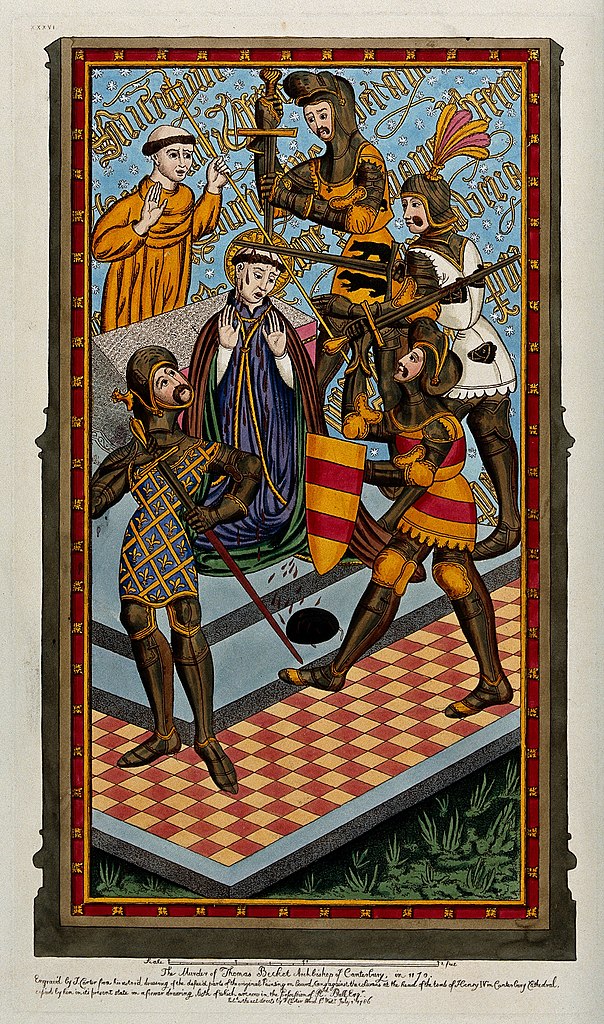

Four knights were dispatched to arrest Thomas Becket. He resisted and fled to the church for sanctuary. Weapons drawn, the knights burst in, violating the sanctity of the church, and slew Thomas Becket. Some accounts treat this event as a premeditated murder, while others believe that Becket’s death was the result of a skirmish that got out of hand during his attempted arrest. Most versions of the attack depict the knights as slicing off the crown of Becket’s head and scattering his brain onto the floor. It was a gruesome murder that would send shockwaves through medieval Europe and threaten the tenuous relationship between church and secular authorities.

More criminal history: The Birdman of Alcatraz

The Making of a Saint

Many contemporaries were disgusted with Henry II’s actions. It is often hotly debated whether Henry intentionally ordered Thomas Becket’s assassination. This is unlikely. Or rather, it is unlikely that a shrewd political mind like Henry II would intentionally order the very public slaying of a major seat of religious power within the sacred halls of the church. If this truly was Henry II’s intention, then he suffered a lapse in judgment. The optics were terrible and they placed Henry in an extremely difficult position. As tedious as Thomas Becket was to contend with in life, in death he became a martyr; an unimpeachable symbol of the nobility of the clergy and the dangers of overreach by secular powers.

But Henry II was both patient and clever. When it was demanded that he arrest Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy and Richard le Breton, the four knights who killed Thomas Becket, he claimed to be unable to do so. International pressure mounted as news of Thomas Becket’s murder spread like wildfire, but the papacy was in no position to take a hard stance against the king of England. Instead, the Pope’s desire for European powers to lend their strengths to the crusades allowed Henry to reconcile with the church rather quickly by agreeing to a compromise that mandated that the King of England go on a crusade. Henry agreed, but he never did actually participate in a crusade in his lifetime. The scandal was a shadow over Henry’s reign, but it did not extinguish the flame of empire that Henry had spent his life stoking.

Meanwhile, the martyred Thomas Becket became a saint in his own right, with a “cult of Becket” that formed around venerating his sacrifice. He was officially canonized just two years after his death. A shrine was built in Canterbury Cathedral, honoring the fallen saint. This would become a famous pilgrimage destination.

Bizarrely, Thomas Becket became something of an unofficial patron saint for Henry II’s descendants. Though it was by the order of their ancestor, later Plantagenet kings would invoke Becket’s martyrdom and Henry II himself made a spectacular show of his regret and penance for the Archbishop’s death. He became something of an unlikely symbol of the humility of the Plantagenet kings and their respect for the church.

More interesting history: The Lost Dauphin