The Cheese and the Worms by Carlo Ginzburg is a fascinating glimpse into the private lives and personal beliefs of the Renaissance commoner. This human-centered history presents the story of a miller who committed the unthinkable crime of developing and sharing his own personal cosmology.

Human History

Before exploring the specifics of what makes this book and its subject so fascinating, I want to discuss why the very concept of this book is a breath of fresh air to me. Written in 1976 by Carlo Ginzburg, who is an acclaimed Italian historian, The Cheese and the Worms dares to insist that the lives of ordinary people are as vital to our understanding and appreciation for the past as those of world leaders. Furthermore, Ginzburg sets out to prove that the inner lives of these “common folk” are as rich and fascinating as any human being’s.

The Cheese and the Worms is an act of rebellion against the “Great Men” theory of history. For the uninitiated, this way of looking at history posits that history is largely made by so-called “great men.” That is to say that leaders, innovators, generals, and other movers and shakers progress the plot of history. If one is to study history, then, one should take a deep look into the lives of these influential individuals. (1)

In recent years, many students and teachers of history have begun to take a more holistic approach. It is not uncommon for this new wave of historian to proudly announce that students in their class will never have to memorize names and dates. Unfortunately, these broad strokes overviews of history often amount to very little actual learning. Discussing the abstract themes of history without understanding the facts, boring though they may seem, is largely pointless. It is like studying the concept of long division before learning to count.

So, is there a study of history which allows us to escape the “great man?” Honestly, probably not, or at least not entirely. Very often, the decisions of world leaders are events which shape humanity’s past and future for better or worse. Understanding the geopolitics of 1940s Europe is simply not going to work if you recoil from studying the career of Winston Churchill. Luckily, there is a solution to this dilemma. Studying the lives of history’s “great men” should be a tool which gives us the context necessary to study all of human history. Humanity’s history belongs to all of humanity and all of humanity is a part of it.

Most history is hidden, locked away in oral traditions that have long died and lives that were simply never recorded. The practice of “microhistory,” which Carlo Ginzburg is credited with helping to found along with several Italian historians from the late 1970s, focuses on researching and writing accurate and detailed accounts of small scale historical events. Often, these events have little influence outside of the lives of those affected while contrastingly demonstrating the immense influence of the atmosphere of the wider world around them. Thanks to people like Menocchio, microhistory gives us an incredibly valuable look at the ordinary lives of our predecessors. Rather than honing in on the “great men,” this methodology looks at how these leader’s decisions have impacted the daily lives of individuals. While records may not allow us to study the details of every single life, microhistory treats each life as worthy of study to whatever degree is possible. (2)

It is the greatest compliment that I can imagine giving to Ginzburg’s work that it approaches the life history of an, admittedly eccentric, Renaissance commoner with the care, fascination, and attention to detail that would be expected in the biography of a “great man.” Menocchio’s quirky worldviews and occasionally radical teachings only serve to reveal the unique personalities and experiences belonging to the faceless mass of “common folk” which have inhabited this planet since before the advent of history itself and yet, have been largely unexamined by historians.

Further Reading: The Bizarre and Mysterious Travel Memoir from the Middle Ages That Features Dragons, Giants, Monsters, and More

Who is Menocchio?

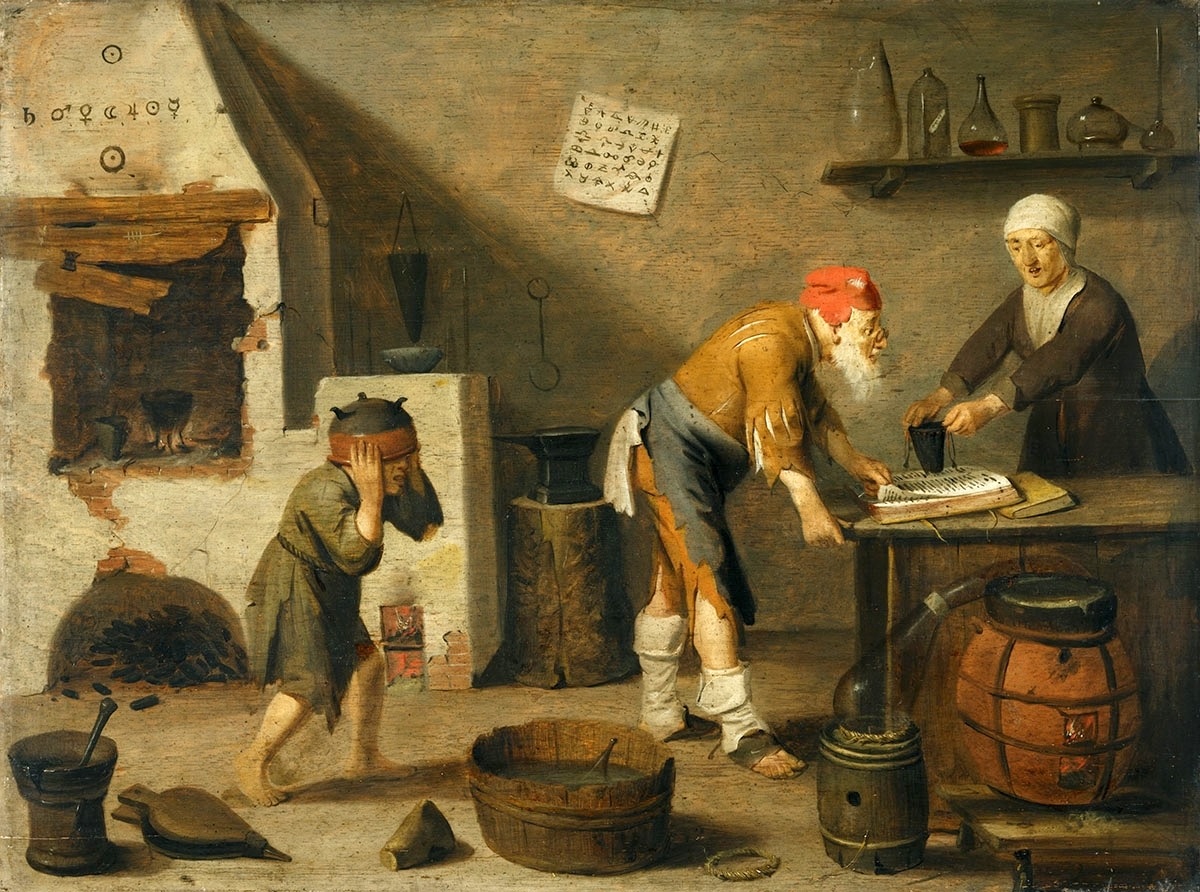

Menocchio, to his credit, is an excellent subject for microhistory. Domenico Scandella, who is referred to as Menocchio throughout The Cheese and the Worms, lived from 1532 until his death in 1599 in a small town called Montereale in the Friuli area of Italy. (3)

Menocchio was a surprisingly well-read man. Ginzburg notes that through his own writings and through the details of his trials, a list of books which Menocchio read can be formed. One of the books that most inspired Menocchio was the popular and bizarre tome, The Voyage and Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Knight.

Although Menocchio’s life would take a turn towards scandal in his last fifteen years, prior to this he seems to have lived a quiet life. Ginzburg reports that Menocchio refers to himself as poor, but that he was at one point the mayor of his town and the surrounding areas. While certainly not rich, it seems that Menocchio was comfortable and had a modest measure of influence within his small community. (4)

Menocchio becomes a fascinating subject of study when, despite the religious orthodoxy of sixteenth century Italy, he begins formulating and sharing his personal cosmology. Menocchio’s apparent curiosity and interest in the nature of the universe is the source of Ginzburg’s title as well as the cause of Menocchio’s own downfall.

What is the Cheese and Who are the Worms?

According to this 16th century commoner, the universe began in a state of chaos. Water, fire, earth, and air were all mixed together without order or reason. Then, Menocchio posits, a mass began to form from these disordered elements “just as cheese is made out of milk.” Then, within this cheese, “worms” began to form. These “worms” were formed from the mass and became the angels. The greatest of these angels was God. The “worms” formed with the ability to move throughout the universe’s “mass” as worms move freely through a block of cheese. (5)

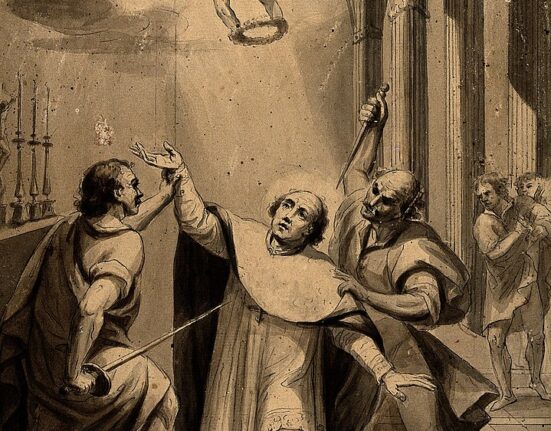

This is just one of many incredible ideas that Menocchio holds and professes. At other times throughout The Cheese and the Worms, Menocchio doubts the sacraments, argues that Jesus cannot have been born from a virgin, and argues that all men are God. Clearly, Menocchio was a free-thinker. These beliefs, his tendency to share them with others, and his ownership of a prohibited copy of the Bible in the vernacular, all contributed to accusations of heresy. These accusations would result in an inquest in 1583 which would see Menocchio spend almost two years in jail despite renouncing his previous statements. (6)

After this, Menocchio would claim to trust in the teachings of the church, but seems to have been unable to sate his curiosity about the universe and appetite for discussion. Some fifteen years after the original inquest into his heretical beliefs, Menocchio once again fell under the piercing gaze of the inquisition. This time, he could not talk his way out of the danger he was in. Domenico Scandella, known as Menocchio, was executed via burning in 1599. Were it not for the surviving records of his trials and select remaining articles of his own writing, Menocchio might have taken his history and his vision of the cosmos, with him into death. (7)

More Weird History: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe and the Mysterious Life He Led

Final Thoughts

As this is a review, I want to end with my overall impression of this book. As a book, I will note that The Cheese and the Worms follows a lot of unexpected tangents and is not as sequential in discussing the events of Menocchio’s life as one might expect. As a result, it is not easy to reference quickly and it can be difficult to place its passages into chronological context. Some of the confusion I felt while following the narrative of The Cheese and the Worms might be reasonably chalked up to translation though, as the original manuscript is Italian. For such a slim volume, I would struggle to classify this text as “light reading,” but as far as criticisms go that is all I have.

At this point, I’d like to once again gush about the concept of “microhistory” and the humanism inherent to this methodology. With the population of this planet always expanding, and with so many more human lives recorded via the advances of the information age, it is inevitable that before long we will have to confront the realities of constructing our lives atop the billions of graves of those who came before us. It is only right that we should treat these past humans with the dignity and interest that we can only hope to receive from future generations. As “commoners” ourselves, it is untenable that we should go on studying nobody but the “great men” who have been credited with bringing us to this point. In studying the common people we are studying ourselves. To do so can only afford us greater insight into the human condition, as Menocchio himself has proven.

More than anything else, The Cheese and the Worms has left me with a nagging curiosity. If a humble miller like Domenico Scandella held such radically non-conformist beliefs, how many more people from our past have looked up at the sky and imagined a cosmology of their own? Thinking about all of these imaginary universes is strangely comforting. It reminds me that history is not as distant as it sometimes seems.