Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle was first published as a magazine serial 1905. It was subsequently released as a novel in 1906, after which it quickly became a bestseller. Its impact upon United States legislature was almost immediate. Sinclair’s novel, however, was written with a different purpose in mind.

Who is Upton Sinclair?

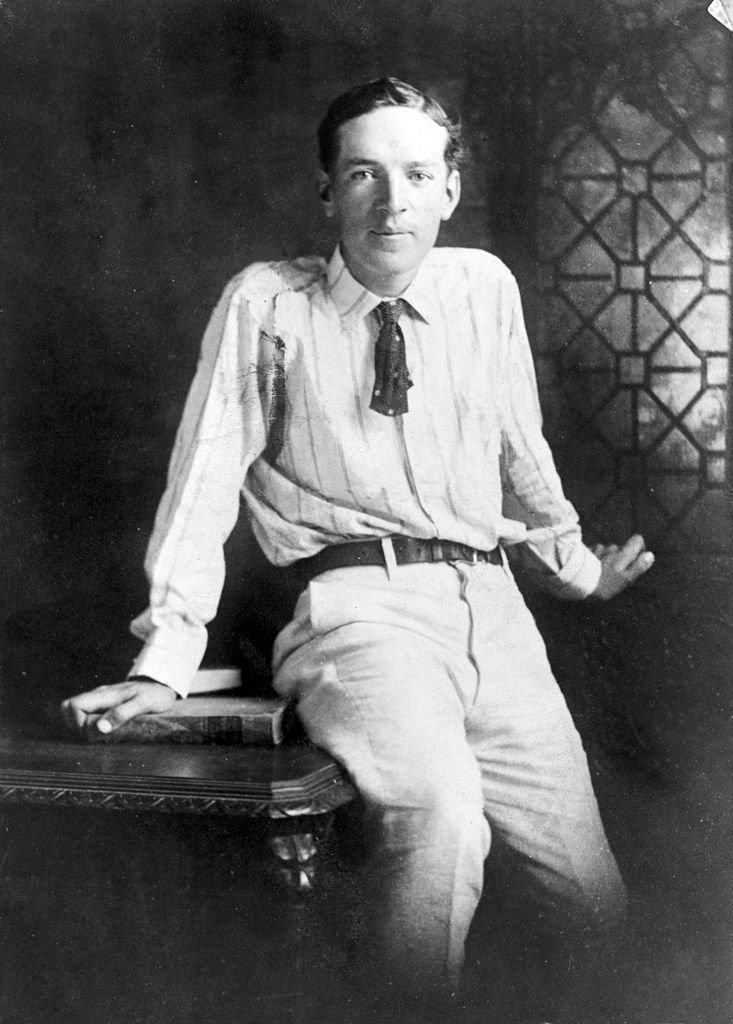

Upton Sinclair is most famous for The Jungle, but his career actually began as a writer of adventure stories which he sold to various magazines during his college years. Sinclair was born in 1878 in Baltimore, Maryland to a Southern family whose fortunes had been humbled by the relatively recent conclusion of the Civil War. As a young writer, Sinclair struggled to get by, despite his being exceptionally prolific. His financial struggles undoubtedly contributed to Sinclair’s eventual infatuation with socialism. (1)

In 1903, Sinclair joined the Socialist Party and began writing for a socialist magazine known as Appeal to Reason. While working for Appeal to Reason, Sinclair became further convinced of the necessity of socialism as he witnessed the ongoing poor working conditions in factories, unionization efforts, worker strikes, and general tumult brought on by widespread industrialization. In 1904, a meat-packer’s union strike, which was ultimately unsuccessful, prompted Sinclair to investigate the conditions of the meat-packing industry. Sinclair spent seven weeks undercover investigating factory conditions for the fictionalized journalistic account which would become The Jungle. (2)

The Jungle

The Jungle follows the harrowing, brutal, and entirely tragic life of a man name Jurgis Rudkus, his wife, Ona, and their struggling family. Jurgis and Ona are immigrants from Lithuania who have come to the United States in search of opportunity. While they are initially delighted to have found jobs in “Packingtown,” Chicago’s meat-packing slum, the two are quickly scammed and squeezed out of their meagre funds. Before long the family, down to even the young children, must work in Packingtown’s factories in order to make the necessary payments on their home.

Jurgis works in a meat-packing plant in which he bears witness to the disgusting and unsanitary food-handling practices therein. These practices are laid out in the infamous fourteenth chapter of the novel. The most egregious sections are quoted below. (3)

Jonas had told them how the meat that was taken out of pickle would often be found sour, and how they would rub it up with soda to take away the smell, and sell it to be eaten on free-lunch counters ; also of all the miracles of chemistry which they performed, giving to any sort of meat, fresh or salted, whole or chopped, any color and any flavor and any odor they chose.

Page 135 of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle

It was only when the whole ham was spoiled that it came into the department of Elzbieta. Cut up by the two thousand-revolutions-a-minute flyers, and mixed with half a ton of other meat, no odor that ever was in a ham could make any difference. There was never the least attention paid to what was cut up for sausage ; there would come all the way back from Europe old sausage that had been

Page 136 of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle

rejected, and that was mouldy and white it would be dosed with borax and glycerine, and dumped into the hoppers, and made over again for home consumption. There would be meat that had tumbled out on the floor, in the dirt and sawdust, where the workers had tramped and spit uncounted billions of consumption germs. There would be meat stored in great piles in rooms ; and the water from leaky roofs would drip over it, and thousands of rats would race about on it. It was too dark in these storage places to see well, but a man could run his hand over these piles of meat and sweep off handfuls of the dried dung of rats. These rats were nuisances, and the packers would put poisoned bread out for them ; they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together. This is no fairy story and no joke ; the meat would be shoveled into carts, and the man who did the shoveling would not trouble to lift out a rat even when he saw one—there were things that went into the sausage in comparison with which a poisoned rat was a tidbit. There was no place for the men to wash their hands before they ate their dinner, and so they made a practice of washing them in the water that was to be ladled into the sausage. There were the butt-ends of smoked meat, and the scraps of corned beef, and all the odds and ends of the waste of the plants, that would be dumped into old barrels in the cellar and left there. Under the system of rigid economy which the packers enforced, there were some jobs that it only paid to do once in a long time, and among these was the cleaning out of the waste barrels. Every spring they did it; and in the barrels would be dirt and rust and old nails and stale water—and cartload after cartload of it would be taken up and dumped into the hoppers with fresh meat, and sent out to the public’s breakfast.

As revolting as these passages are, the life of Jurgis was intended by Sinclair to be even more disturbing. Despite initially championing his employers, the dangerous conditions of the factories eventually lead Jurgis to support the unions. Despite the constant physical pain he describes as resulting from his relentlessly laborious work, Jurgis cannot afford to seek alternative employment. Ona is forced to enter the work force due to the family’s financial desperation. There she is sexually assaulted by her employer and forced to comply at the threat of losing her job. The physical hazards of the factory also cause her to contract a cough which weakens her until she eventually dies in childbirth. Jurgis, left with his small child to care for, sinks into alcoholism. Shortly after this, Jurgis begins working a a steel mill where he is grievously injured. The living conditions in Packingtown are so putrid and terrible that the streets are often flooded. Jurgis and Ona’s young son drowns in the street while Jurgis is away at work. (4)

After this, Jurgis is once more injured at another job and is finally too physically broken to labor. He begs for money in the streets and is drawn into a life of petty crime. After a series of criminal ventures and failed attempts to get his life on track once more, Jurgis is penniless, hopeless, and utterly alone. It is then that he happens upon a socialist rally. From then on, Jurgis embraces the Socialist Party, his fortunes begin to gradually reverse, and his outlook becomes hopeful. (5)

America’s Stomach

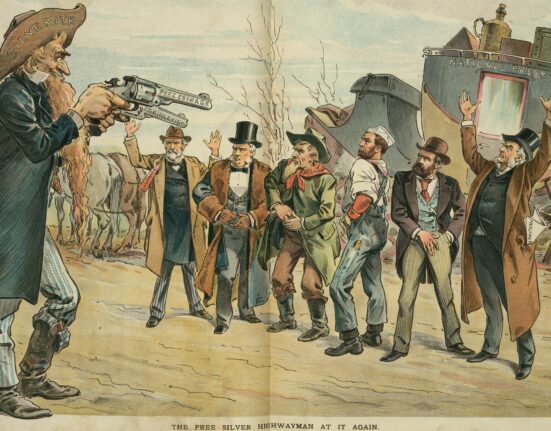

The Jungle was an instant success and it did not take long for the shock, horror, and disgust that Sinclair had hoped for to begin pouring in. To Sinclair’s surprise, however, this indignation largely ignored Jurgis, Ona, and the real families just like theirs who toiled in Chicago’s factories. Instead, the American public was horrified by the glimpse into the meat-packing process. Hundreds and hundreds of letters from concerned citizens began arriving at the White House within the first month after The Jungle was published. People began to demand regulations within the food industry at the Federal level. (6)

In Sinclair’s own words: “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” Despite Sinclair’s fervent efforts to draw the public’s attention to the human aspects of his story, its most significant lasting impact was and continues to be the widespread reforms of the meat-packing and general food-handling industries which followed its publication. (7)

In 1906, again just months after The Jungle was published, Theodore Roosevelt signed the Food and Drugs Act as well as the Meat Inspection Act. Issues with lack of quality control and false advertising across multiple industries contributed to the formation of the FDA, but The Jungle was undeniably a driving force behind its existence and, perhaps more importantly, behind the public’s interest in and acceptance of this new act. (8)

Sinclair remained an outspoken socialist voice throughout his long life, at one point even running as the Socialist Party candidate for governor in California. He is remembered as one of the most famous “muckrakers” in United States history and was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1943 for yet another journalistic novel. His persistence, integrity, and unflinchingly candid look into the dark underbelly of an industry which affected nearly every American paved the way for generations of whistleblowers and journalists to come. (9)